A Teacher's Guide to Talking About Hate in America.

Source: Washington Post

By: Valerie Strauss

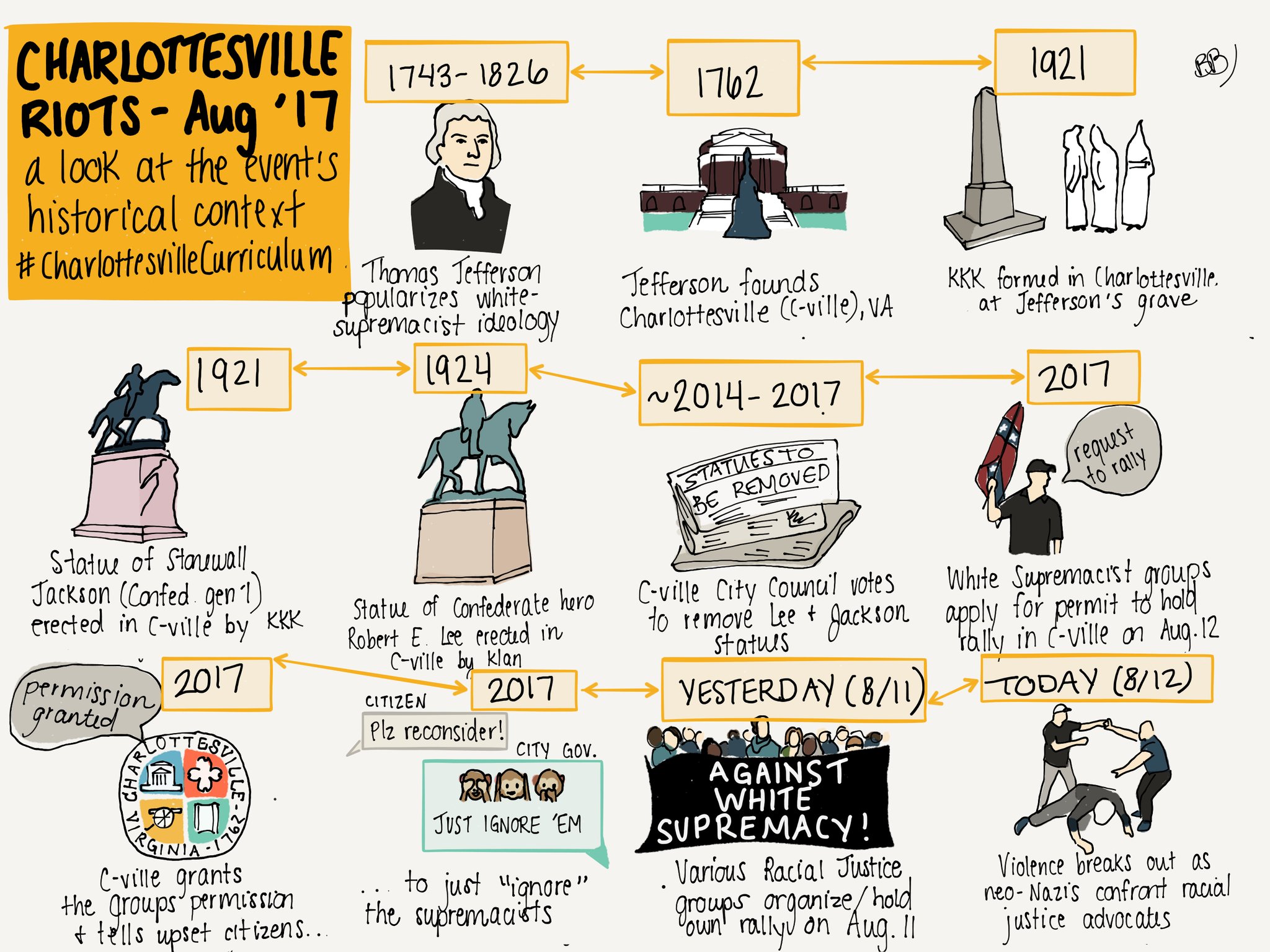

#CharlottesvilleCurriculum: That’s the new Twitter hashtag for educators, parents and anyone else looking for resources to lead discussions with young people about the violence that just erupted in Charlottesville, when white supremacists, neo-Nazis and Ku Klux Klan members marched and clashed with counterprotesters. One woman was killed and 19 were injured when a car rammed into the counterprotesters, and two state police officers assisting in the response died when their helicopter crashed on the outskirts of town.

The 2017-2018 school year is getting started, and teachers nationwide should expect students to want to discuss what happened in Charlottesville as well as other expressions of racial and religious hatred in the country.

While such discussions are often seen as politically charged and teachers like to steer clear of politics, these conversations are about fundamental American values, and age-appropriate ways of discussing hatred and tolerance in a diverse and vibrant democracy are as important as anything young people can learn in school. Civics education has taken a back seat to reading and math in recent years in “the era of accountability,” but it is past time for it to take center stage again in America’s schools.

The white supremacists, neo-Nazis and Ku Klux Klan staged their largest rally in decades to “take America back,” displaying Confederate and Nazi flags as they targeted every minority in the United States. Given that the population of students in America’s school are now majority-minority, that’s a lot of young people.

The hashtag #CharlottesvilleCurriculum was started by Melinda D. Anderson, a contributing writer to the Atlantic, who wrote in an email:

“I started the hashtag for a very simple reason: I know that in these situations a common reaction by educators is, ‘What should I say? Where do I even begin? I also know that lots of educators are on Twitter – and they look to the platform to connect and learn. So I wanted to create a way to crowdsource resources that would help them begin to explore the historical underpinnings of white supremacy and use the materials to help bring context and clarity to Saturday’s events in Virginia — so they could carry that back to their classrooms and schools.

Teachers are already posting some material on Twitter:

The American Federation of Teachers has also collected links for teachers, here, and below is a detailed guide from the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance program on how teachers, counselors and administrators should respond to hate and bias when they are manifested in school. Teaching Tolerance offers a long list of resources for educators, with lessons plans and other material. You can find all of that here.

Detailed Guide From the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance Program:

Here are materials from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum for educators, complete with lesson plans and other resources, and below is a full lesson on hate crimes from Teaching Tolerance, which is offering an Educator Grants program that will provide $500 to $5,000 for projects that educate students to thrive in a diverse society, promote a positive and affirming school climate, and help marginalized students. Educators who work in public or private K-12 schools, as well as alternative schools, therapeutic schools and juvenile justice facilities, are eligible to apply at tolerance.org/about/educator-grant-guidelines[tolerance.org]. Applications will be accepted and reviewed on a rolling basis.

Teaching Tolerance Full Lesson on Hate Crimes:

Activities meet the following objectives:

- understand the definition of “hate” and be able to use alternate words

- discover and understand how national laws are made

- apply that understanding to the concept of government protection

Essential questions

- What is the nature of hate?

- What is the statistical picture of hate crimes in America?

- How does the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act expand protections against hate crimes?

- Who were Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr.?

- How does the new law compare to previous hate-crimes legislation?

Materials

Pencil and paper

Internet accessVocabulary

hate |hāt|

(noun) A strong feeling of dislike.

(verb) To strongly dislike.crime |krīm|

(noun) An act or behavior that breaks a law. A crime is usually punished by a fine or prison time.law |lô|

(noun) A rule that helps keep order within a society.legislation |ˌlejəˈslā sh ən|

(noun) A law or laws passed by a government body.Procedure

Reading/Language Arts/ELL

1. The word “hate” is a strong one. But we often use it in a casual way. Think about the times you have used it to describe your reaction to something.

- Now, make a list of the things you “hate.” (Examples might include things like broccoli, homework, rainy days or getting up early.) Does your list include any people? What’s the difference between hating a thing and hating a person?

- As a class, discuss the definition of the word “hate.” (The word refers to a feeling of strong dislike — a feeling that demands action.) What can happen when somebody acts on their feelings of hate? Discuss how those actions might impact your classroom, your school and your community.

- Partner with another student or a small group of students. Take turns rephrasing your “I hate …” sentences so that they include more specific information. For instance: Instead of saying “I hate broccoli,” consider saying, “Broccoli doesn’t taste good to me” or “I like carrots better than broccoli.” If your list includes people, consider saying, “I wish my sister shared her toys” rather than “I hate my sister.” Why do you think these sentences are better choices? Share some examples of your new sentences with the rest of the class.

- As a class, agree that you will keep checking your use of the word “hate.” Every time you hear it or read it, stop and think about it. If possible, discuss it with a classmate or friend. How would you rephrase the sentence?

Social Studies

1. As a class, brainstorm examples of rules that you live by every day — at home, school and in your community. Discuss some reasons for these rules or laws. (Examples might be traffic laws intended to keep drivers safe, school rules that help keep students and teachers focused on learning, or laws in your community that protect its citizens from others who might harm them.)

- At the national level, Congress has the power to make laws. Congress represents the legislative branch of the U.S. government. Divide the class into three groups. Within your group, use the Internet to access the federal Ben’s Guide to U.S. Government for Kids.

- Each group will have responsibility for researching and sharing information about one of the following:

- What Is a Law?

- Who Makes Laws?

- How Laws Are Made?

Within each group, take notes on the information needed for your group’s presentation.

- Present your information to the entire class. After all groups have presented, review the process from the time a bill is introduced to the time it is signed by the president.

- President Barack Obama signed a law that would help protect Americans against hate crimes. (Note: You may want to explain a bit about this law.) A hate crime is an attack against somebody because of their differences, such as skin color, religion or disability. The law is called the Hate Crimes Prevention Act. Together, brainstorm ways this law might affect the everyday lives of people in your community. Using it as an example, evaluate the reasons that we have laws. Why are they important?

Political Cartoon Lesson on Hate:

In this editorial cartoon, artist Daryl Cagle depicts a group of students expressing “hate” for an undisclosed group of people. In pairs or small groups, discuss:

- What message is he trying to convey about the nature of hate? In this case, what word would you use to describe the group? (Examples: ignorant, unaware or uneducated.) How might their conversation be different if they had accurate information or a better understanding about “them?” Act out the conversation you imagine, or redraw the cartoon to reflect it.

- This cartoon was originally drawn on Sept. 13, 2001. Based on this information, who might have been the “them” to which Cagle refers? If you are unsure, ask older students or family members what they recall about that time. What reaction to this group of people does Cagle’s cartoon describe? As a class, discuss whether these attitudes have changed since the cartoon was first drawn. If so, how? What might have caused those attitudes to change?

External Links

Preventing Youth Hate Crime: A Manual for Schools and Communities

LESSON

Critiquing Hate Crimes Legislation

This lesson leads students to analyze the nature of hate and explore legislation that addresses hate crimes.